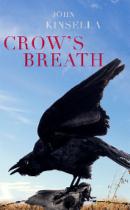

One of Australia’s foremost poets brings inventiveness and economy to this clever collection of microfictions.

Crow’s Breath, John Kinsella’s new collection of short stories, opens with an uncommonly wise eight-year-old walking home from the school bus stop when his mother doesn’t come to pick him up. Alone by the side of the road, he watches an enormous wedge-tailed eagle circling above him and he’s reminded of the name his mother secretly calls him when his father’s not around – my little lamb.

For a moment, the child is paralysed with ‘fear and wonder’ before his mother pulls up in the car, a flustered whirlwind of sincere apologies and kind words. ‘Now let’s get home and have some afternoon tea,’ she tells her little lamb, ‘Then you can play until dinner. I’ve got your favourite.’

The story ends here, but the vulnerability and the uneasiness linger. Kinsella’s purposefully off-key dialogue (‘I’ve got your favourite’) lets us know that what was once safe is no longer safe. And that’s all in the space of barely four and a half pages.

As brief as daydreams, but not always as pleasant, the 27 short stories that make up Crow’s Breath are bound together by themes as diverse as loneliness, frailty and distance. Kinsella, one of Australia’s foremost poets, brings a poet’s inventiveness and economy to this clever collection of microfictions. Some stories are simple sketches of a moment in time – like ‘Metronome’, in which the narrator remembers visiting his girlfriend’s house as a teenager and watching her play the accordion under the intense glare of her grandmother. In ‘The Monitor’, Kinsella somehow manages to squeeze an entire life into a mere nine pages.

In Crow’s Breath’s strongest stories, Kinsella sets up a subtle link between landscape and character. Many of his characters are lonely people in equally lonely places. His cast is made up of outsiders and rejects; often people escaping their pasts. In the collection’s second story, ‘The Plough Star and the Fence’, a man uses a tractor to plough a field at night, watching the stars as he contemplates his former life in the city; his escape from his addiction to drugs. In ‘On Display’, a young father makes a new start in a small town and struggles to connect with his shy son during custody visits, until he finds a park with a train engine for the children to climb.

The title story, ‘Crow’s Breath’, is a series of sketches of a tiny town dying from salinity. As the land is choked by salt and baked by the sun, the food in the local store has become rancid and the few people remaining in the town are similarly strange, turning like milk. A girl attempts to bring a dog back to life using electrical wires and buries the corpses of robins in the salt that’s killing the town to preserve their bodies. The town might be dying, but life continues.

Not all of Kinsella’s oddball characters are harmless. In ‘A Particular Friendship’, a farmer is hospitalised and while he’s away, his eight-year-old twins, fascinated by animals, let their pet cocker spaniels, Bluebell and Captain, befriend their father’s kelpies – working dogs, kept in a cage away from the house. When the father returns to find his working dogs domesticated, his reaction is immediate – and brutal:

One of Australia’s foremost poets brings inventiveness and economy to this clever collection of microfictions.

Crow’s Breath, John Kinsella’s new collection of short stories, opens with an uncommonly wise eight-year-old walking home from the school bus stop when his mother doesn’t come to pick him up. Alone by the side of the road, he watches an enormous wedge-tailed eagle circling above him and he’s reminded of the name his mother secretly calls him when his father’s not around – my little lamb.

For a moment, the child is paralysed with ‘fear and wonder’ before his mother pulls up in the car, a flustered whirlwind of sincere apologies and kind words. ‘Now let’s get home and have some afternoon tea,’ she tells her little lamb, ‘Then you can play until dinner. I’ve got your favourite.’

The story ends here, but the vulnerability and the uneasiness linger. Kinsella’s purposefully off-key dialogue (‘I’ve got your favourite’) lets us know that what was once safe is no longer safe. And that’s all in the space of barely four and a half pages.

As brief as daydreams, but not always as pleasant, the 27 short stories that make up Crow’s Breath are bound together by themes as diverse as loneliness, frailty and distance. Kinsella, one of Australia’s foremost poets, brings a poet’s inventiveness and economy to this clever collection of microfictions. Some stories are simple sketches of a moment in time – like ‘Metronome’, in which the narrator remembers visiting his girlfriend’s house as a teenager and watching her play the accordion under the intense glare of her grandmother. In ‘The Monitor’, Kinsella somehow manages to squeeze an entire life into a mere nine pages.

In Crow’s Breath’s strongest stories, Kinsella sets up a subtle link between landscape and character. Many of his characters are lonely people in equally lonely places. His cast is made up of outsiders and rejects; often people escaping their pasts. In the collection’s second story, ‘The Plough Star and the Fence’, a man uses a tractor to plough a field at night, watching the stars as he contemplates his former life in the city; his escape from his addiction to drugs. In ‘On Display’, a young father makes a new start in a small town and struggles to connect with his shy son during custody visits, until he finds a park with a train engine for the children to climb.

The title story, ‘Crow’s Breath’, is a series of sketches of a tiny town dying from salinity. As the land is choked by salt and baked by the sun, the food in the local store has become rancid and the few people remaining in the town are similarly strange, turning like milk. A girl attempts to bring a dog back to life using electrical wires and buries the corpses of robins in the salt that’s killing the town to preserve their bodies. The town might be dying, but life continues.

Not all of Kinsella’s oddball characters are harmless. In ‘A Particular Friendship’, a farmer is hospitalised and while he’s away, his eight-year-old twins, fascinated by animals, let their pet cocker spaniels, Bluebell and Captain, befriend their father’s kelpies – working dogs, kept in a cage away from the house. When the father returns to find his working dogs domesticated, his reaction is immediate – and brutal:

So he poisoned them. Strychnine. He killed the kelpies. He killed Bluebell and Captain. He fed them baited meat and watched them die. Their death throes looked like a bizarre game, something the twins would play. It has to be said, his children were odd.

It took him hours to drag the corpses to the well … His wife pleaded with him not to tell the children. When the twins, home from school, rushed in calling, Where are the dogs? he just said, They’re gone. And keep away from the old well.

As cruel as nature can be, human nature is crueller. Crow’s Breath also focuses on horrors of a more supernatural kind. Kinsella’s horror stories are among his best. ‘In Necrospect’ is a spectacularly creepy tale about two teenagers who break into a local squat, and in ‘The Sleeper’ a man who never sleeps travels across Australia by train. He watches the landscape moving past and, as night falls, finally decides to sleep:Through the window he could see the stars – many more than had been named, than had been charted. He could see all the stars to be seen in that part of the sky. He could see the stars as if through daylight. And then he forgot who he was and forgot what wakefulness is. Was.

In the second half of Crow’s Breath, Kinsella begins to move away from the Australian landscape and out into the world. In ‘The Statue’, a middle-aged Australian farmer who has recently lost his wife travels to London, where he falls in love with a marble statue in a museum. The eerie ‘Binoculars’ is set on the Irish coast, while in ‘Golden Gloves’, we flash between Carnarvon, Geraldton and Ohio. But as Kinsella’s narratives shift their focus to the world at large, the collection loses a little of its cohesion. Some of the stories towards the end seem less substantial than those that came before. However, with so many highlights, Kinsella’s hits more than make up for his misses. Crow’s Breath is a varied collection of very short stories that are chilling, funny and captivating in turn. Each piece bears the subtle, unmistakable fingerprint of one of our finest writers at work. John Kinsella Crow’s Breath Transit Lounge 2015 PB 256pp $25.95 Michelle McLaren is a Melbourne-based copywriter who blogs about books at Book to the Future. You can buy this book from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here. To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.Tags: Australian fiction, Australian short stories, John | Kinsella

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.