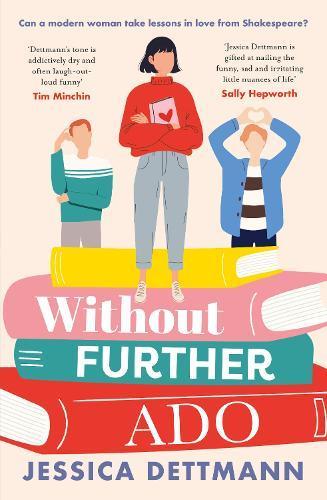

Jessica Dettmann’s third novel reinvents a classic tale of romantic complications to enjoyable effect.

Jessica Dettmann’s Without Further Ado is based an old story – about 400 years old. It was 1600 or thereabouts when Shakespeare is thought to have written Much Ado About Nothing, a play in which – as the title reveals – drawn-out chaos ensues over a silly mistake that shouldn’t have raised its ugly head in the first place. It’s very much the kind of situation that attracts outpourings of frustration on forums such as Reddit, when a misunderstanding that could have been cleared up in two minutes ends up taking three hours of mayhem and melodrama to resolve.

In the original Much Ado, young sixteenth-century woman Hero is publicly rejected by her betrothed when he is tricked into thinking he witnesses her being indiscreet with another man. In Without Further Ado, young twenty-first-century Imogen is rejected by her fiancé, Angus, who mistakenly believes she has had a particularly enjoyable hen’s night with a male stripper.

Imogen’s cousin Willa, who has long been obsessed with the 1993 Kenneth Branagh–Emma Thompson film of the Bard’s tale, finds herself occupying the Beatrice role, having to negotiate Imogen, Angus, his brother Ewan and everyone else through the inevitable plot twists and resultant hilarity towards the eventual happy ending. And she has to do this while continuing to work alongside Angus, Ewan and their two other brothers at their father’s publishing firm, where she runs the entire romance imprint on her own.

Romance was the way to go, she figured, because it made people feel good. Delicious, addictive and formulaic: in big business that was how you made a successful product. Think of Coke, iPhones, Marvel movies … Romance also happened to be a genre she’d always leaned towards as a consumer, in books and film.

Delicious, addictive and formulaic is also what drives stories such as Without Further Ado, where the interest lies not in what happens next but, like others of its type such as Bridget Jones’s Diary or Ten Things I Hate About You, in seeing how characters and situations from the distant past can be translated into more familiar times. For instance, we see the wordplay of Shakespeare’s Beatrice and her nemesis Benedick play out in the repartee between Willa and Ewan that livens up boring office meetings. Shakespeare’s theme of deception and self-deception is reflected in Willa’s habit of sarcasm and her utterly transparent denial of the attraction between them. And the timelessness of people’s obsession with marriage – do they want to, who they want to do it with, the generation of children – remains almost unchanged.

There is nothing wrong with a fun romp of likeable characters through a familiar plot. We know pretty much from its opening pages how this one is going to go. Boy will meet girl. Boy will be manipulated into distrusting girl. Girl will pretend to die / pretend that boy never existed; boy will feel sorry and the stupid misunderstanding will be resolved. Subplot boy and subplot girl, who are already known to each other, will be brought together by the protagonists’ quarrel to realise that what they thought was hate is actually love. Cue happy endings.

The difficulty with this device – despite the constancy of human emotion and experience – is that sexual politics has moved on somewhat since Shakespeare’s day. To the Bard’s audiences, marriage in and of itself constituted such a happy result that it didn’t matter what tawdry path the participants had to travel to get there. In fact, the more unreasonable the journey, the larger the comic effect. Accusing your beloved of infidelity – or being, in Angus’s words, ‘a lying slut’ – would just make the payoff all the more satisfying. Today, however, such behaviour is not only likely to be reported all over social media, but will get the perpetrator cancelled into the bargain.

But Dettmann is deft in the management of this translation. The resolution is satisfying without being compromising, and the blame squarely placed where it’s deserved. Because, although Shakespeare is renowned for universal and timeless themes, his audiences do have a choice. We do not have to be bound by centuries-old norms and can choose our own path. In the words of Willa’s mother:

‘It’s such an awful, awful story,’ she said. ‘They’re all angry at each other for the wrong reasons. There’s so much miscommunication. And don’t get me started on the parenting. I don’t think there’s a worse father in Shakespeare than Leonardo … [his] daughter gets slandered and he attacks her … What a bloody disgrace.’

Jessica Dettmann Without Further Ado HarperCollins 2023 PB 368pp $32.99

Sally Nimon once graduated from university with an Honours degree majoring in English literature and has hung around higher education ever since. She is also an avid reader and keen devourer of stories, whatever the genre.

You can buy Without Further Ado from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW or you can buy it from Booktopia.

You can also check if it is available from Newtown Library.

If you’d like to help keep the Newtown Review of Books a free and independent site for book reviews, please consider making a donation. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Tags: Australian fiction, Australian women writers, contemporary fiction, Jessica | Dettmann, Much Ado About Nothing

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.