David Lindenmayer’s homage to the beauty of the Victorian Central Highlands and Meg Lowman’s memoir of a career spent among the treetops both explore the importance of our forests.

These two books are very different but the purpose of both is the same: to immerse us in the fascinating world of trees and to convince us of their importance, especially in old-growth forests, for our health, wellbeing and, ultimately, our survival.

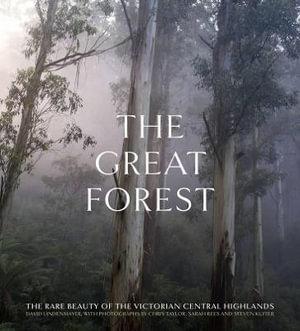

The Great Forest is a beautiful book, handsomely bound and full of stunning photographs. These, interspersed with occasional pages of explanatory text, show us the land, trees, plants and animals of the Central Highlands that rim the city of Melbourne in Victoria. These are some of the tallest forests in the world, some 600 million years in the making, and provide the people of Melbourne with nearly all their drinking water. Sadly, they have been targeted for extensive logging for over a hundred years.

The photographs show the rolling landscape of mountain ranges, ancient crags and rocky outcrops; the waterfalls, streams, and fens; the unique shapes, colours and heights of the trees; and the rich and strange understorey of tree ferns, wattles, fungi , mosses and lichens. They also show some of the unusual animals that live in the forests, many of them nocturnal, so rarely seen.

The contorted shapes of snow gums in sun and in snow display the rich olive, salmon and white colours of their bark. The tallest moss in the world grows on the forest floor; the eerie iridescent green of the ghost fungus lights up the night; and mountain brushtail possums eat the hallucinogenic fungi growing on the trunks of mountain ash. The huge, soaring mountain ash, ‘the tallest flowering plant in the world’, can reach 90 to 100 metres in height, and one archival photograph from 1933 shows all the inhabitants of the village of Fernshaw gathered around the great girth (measured at 19.5 metres) of one of these giants, where they look like little elves in a fairytale.

The amazing variety of these photographs leads, at the end of the book, to scenes of destruction and devastation caused by logging, clear-felling, and by bushfires, which have become fiercer and more frequent in recent years. The contrast is shocking.

David Lindenmayer, who writes the notes that accompany the photographs by Chris Taylor, Sarah Rees and Steven Kuiter, argues for the establishment of a national park to protect this environment, but he writes, too, of the need to restore the health of the forest after the ‘brutal catastrophic damage’ brought by European colonisation, ‘the damaging legacy’ of which ‘lasts to this day’. Old-growth forests generate more water than younger trees, and are more resistant to fire, but 98 per cent of the forests are now less than 80 years old, so it is ‘critical that we start now’ to protect them. ‘We must not forget about the people in small towns and regional areas who make a living from logging forests,’ he writes, but ‘this is not a contest between jobs and the environment. Rather, well-managed conservation is good for all.’ He advocates careful, eco-friendly forest management; training of full-time, professional, firefighters; revegetating key areas; and developing eco-tourism. Importantly, he sees the need for consultation with the local Aboriginal people, who have been the traditional custodians of these forests ‘for tens of thousands of years’.

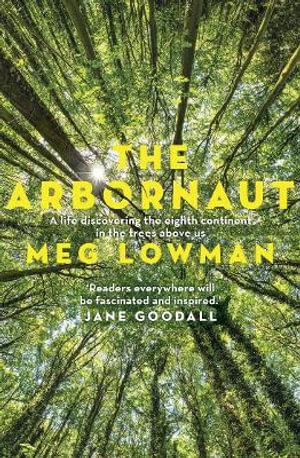

Meg Lowman, the ‘arbornaut’ of her memoir, provides a worldwide perspective on this same subject, writing that:

It shouldn’t be a surprise (but it still is for some) that planetary health links directly to forests. Their canopies produce oxygen, filter fresh water, transfer sunlight into sugars, clean our air by absorbing carbon dioxide, and provide a home to the extraordinary genetic library of all earthbound creatures, among many other crucial functions.

Meg’s passion for studying nature began early when, as a child, she collected wildflowers, pressed them between the pages of telephone books, tried to identify each specimen, and stored the whole collection under her bed, where, to her mother’s distress, it attracted mice. At the age of 11, she won second prize for this collection at the New York State Science Fair. She went on to identify old birds’ eggs her grandfather had collected and, inspired by reading the work of biologist Rachel Carson, she conducted her first simple scientific experiment by comparing the shell thickness of one old hen’s egg from her grandfather’s collection with that of fresh eggs from her mother’s refrigerator.

As a shy, nature-obsessed child she had no-one to share this interest with until her parents agreed to let her attend a summer wildlife camp. There, her enthusiasm grew and she was invited to return the next summer as a junior staff member.

All of these childhood passions, patched together like a quilt, led me to ultimately become one of the world’s first arbornauts. I probably would not have pursued field biology as a career without a halcyon childhood of outdoor exploration. Mostly trees. Mostly solitude. Mostly wildflowers, leaves, and curiosity about how nature operates.

Lowman became one of the first scientists to investigate the tops of trees, the canopy, which, as she notes, is home to ‘upward of half of all terrestrial animals’, and which she dubbed ‘the eighth continent’. She has now spent decades as a scientist exploring this ‘continent’, educating others in this pursuit, teaching and mentoring students, and bringing together a global community of arborealists. She designed and helped to construct the first tree-walk in Australia, and has gone on to work on others around the world. None of this was what she planned to do when she welded together some pipes to make her first slingshot, fired a weighted fishing line into a tree, hauled up a sturdy rope and began to climb. Taking hints from caving friends at Sydney University, she refined her climbing gear and climbed higher, experiencing ‘sensory overload’ on her first climb into a tall Australian rainforest tree:

Beams of light began to flicker on my face as I drew closer to the top of the coachwood. Then mayhem broke loose around me. I had entered the sun-flecked leaves of the official upper canopy … creatures munching, flying, crawling, pollinating, hatching, burrowing, sunning, digesting, singing, mating, and stalking. The life surrounding me was entirely invisible from the forest floor.

Lowman’s career, especially as a woman working in a scientific environment dominated by men, has had its ups and downs (no pun intended), but she has been persistent and innovative and very successful in promoting the scientific study of tree canopies. Ninety-five per cent of the forest exists above ground-level, but until quite recently scientific research has taken place in the understorey and around the trunks of trees. Lowman likens this to having a doctor diagnose the state of your health by examining only your big toe. Her own exploration of this 95 per cent has been laborious and painstaking. In Scotland, in bitter weather, she studied the leafing and flowering pattern of Scottish birch trees and constructed her first rickety platform ‘to survey the tree crowns about twenty-five feet high’. In Australia, she climbed higher and over a period of three years numbered and labelled hundreds of branches and leaves on five different species of rainforest tree to observe seasonal changes and depredation by insects. This included the giant stinging tree, which has hairs with stings 39 times more toxic than the hedgerow stinging nettle.

Lowman writes in a chatty, easygoing way, describing her life, her experiments, her achievements, and her ongoing aim of sharing her story so that others, especially young women, will be inspired to follow their passions and not hesitate ‘to be smart and strong’. Her detailed descriptions of her research were sometimes a little too long for me but they are balanced by glimpses of her personal life, and by vivid accounts of her travels and adventures in the Amazon rainforest, in India and in the Cameroons. Since she began her career, technology has changed the way scientific research is recorded and disseminated and Lowman has adapted to that, now using it to create innovative and important scientific networks, and to link citizen scientists together to collect and record data.

In many ways, The Arbornaut complements and adds to the arguments presented in The Great Forest. I was happy to read Lowman’s clear account of just how forests produce the water that Lindenmayer tells us is so important to us, and glad to learn of the initiatives taken worldwide to increase awareness of the natural environment. Both books also demonstrate the way climate change is affecting the world’s forests, and how essential it is that governments everywhere recognise and address this issue. Careful management of the forests, as Lindenmayer says, ‘is good for all’.

David Lindenmayer The Great Forest: The rare beauty of the Victorian Central Highlands, with photography by Chris Taylor, Sarah Rees, Steven Kuiter, Allen & Unwin 2021 HB 192pp $49.99

Meg Lowman The Arbornaut Allen & Unwin 2021 PB 368pp $32.99

Dr Ann Skea is a freelance reviewer, writer and an independent scholar of the work of Ted Hughes. She is author of Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest (UNE 1994, and currently available for free download here). Her work is internationally published and her Ted Hughes webpages (ann.skea.com) are archived by the British Library.

You can buy The Great Forest from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

You can buy The Arbornaut from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.

If you’d like to help keep the Newtown Review of Books a free and independent site for book reviews, please consider making a donation. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Tags: Chris | Taylor, climate change, David | Lindenmayer, environment, forest canopy, forests, Meg | Lowman, memoir, Sarah | Rees, Steven | Kuiter, trees, Victorian Central Highlands

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.