Catherine Chidgey’s latest novel has been shortlisted for the 2022 Dublin Literary Award and longlisted for the Women’s Prize.

Buchenwald Concentration Camp was liberated by US Forces on 11 April 1945. In the days immediately following, the Americans ordered one thousand citizens of the neighbouring German town to tour the camp and bear witness to the atrocities found on their doorstep. Their first-person-plural narrative – ‘From the private reflections of one thousand citizens of Weimar’ – is one of multiple German wartime perspectives in Catherine Chidgey’s capacious sixth novel Remote Sympathy. Their ‘we’ voice is one of its special, creative threads:

When the Americans told Herr Gräber that we had to come and look at that place up on the Ettersberg, he said the camp was nothing to do with us, and we’d known nothing of what had gone on there. Such a tour would be humiliating, he said, and he pointed out that if Hitler had done evil things, it should be acknowledged he had done good things too. But the Americans were having none of that.

Chidgey has a penchant for re-angled through-lines. The titular narrator in her previous novel, The Wish Child, is also cleverly designed. Both are historical fictions set in the Reich during the Second World War, told from German points of view. Chidgey has a degree in German language and literature; that and her own research and translation of some of the source materials inform these works without burdening them stylistically.

The town of Weimar has two symbolic associations in Remote Sympathy. Geographically, it is next door, conspicuously and complicity close by, approximately ten kilometres from the prison camp. And culturally, it was home to the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1842). The beechwood forest on the Ettersburg mountain was cleared to construct the camp but ‘Goethe’s Oak’ was spared. Chidgey explains the tree’s universal significance in an informative interview with the New Zealand website Jewish Lives. (And family trees are also important to the story.) Weimar represents an olden Germany, a traditional heartland; its one thousand citizens a collective, civic, moral consciousness. The novel’s pointed title is doubly ironic.

The dramatic plot triangulates the interrelationships of SS Sturmbannführer Dietrich Hahn, the camp’s administrative officer; his Catholic wife, Frau Greta Hahn; and Doktor Lenard Weber, a civilian prisoner at Buchenwald. Each reveals themselves in first-person accounts and in so doing we read the perspectives of, respectively, a German war criminal, a German victim, and a German survivor. However it’s more blurred than that, too intelligent for good German or bad German tropes: there are shades of culpability.

The singular event is the Hahn family’s relocation during the war from the familiarity of Munich to the disquiet of Buchenwald. This may be a promotion for the careerist Hahn but it’s a posting to hell which irreparably changes the course of their lives – and their two years at Buchenwald (1943-1945) are contiguous with Germany’s gradual defeat. They move into one of the ten houses on Eickeweg, an almost make-believe street in the forest for the Nazi higher-ups and their families, disturbingly, within walking distance of the camp. It’s a golden cage, a grotesque, hotel-like existence, uncomfortably serviced by prisoners who are exploited for their labour. Greta is entrapped, in effect a prisoner outside the wire, as is the couple’s young son, Karl-Heinz.

Greta is naïve early on but above all is a victim of circumstances. She progressively succumbs to illness and disease and turns back to religion. That’s not to say she’s a weak character. Greta is arguably the one who late in the novel finds the greatest sympathy for another human being, in a selfless act of courage and kindness by one German for another. Whereas Hahn and Weber’s sympathy for each other (if any) is entirely provisional.

Weber is a junior doctor at the Holy Spirit Hospital in Frankfurt – we first meet him in 1930. He is married to Anna Ganz, ‘a Jewess’; and there is a question mark over his maternal grandfather’s ancestry. This becomes an existential problem as National Socialism metastasises in Germany. Matter-of-factly, in March 1939, the couple decide they will divorce (on paper) – to separate and be seen to have annulled their marriage – on the basis that this will somehow protect their young daughter, Lotte.

And Weber may actually believe in miracles: he is the hobby inventor of the ‘Sympathetic Vitalizer’, an electrotherapy machine designed to cure cancer, which he trials on a few terminal patients. His commitment is understandably personal and perversely patriotic: Weber’s father died of cancer, as did Hitler’s mother. Weber/Chidgey explains the pseudo-science behind this on the very first page, as if to quickly get the premise out of the way:

[eighteenth-century Scottish surgeon John Hunter’s] theory that the cure as well as the disease could pass through a person by means of remote sympathy; that the energetic power produced in one part of the body could influence another part some distance away.

The Vitalizer is a metaphor for a desperate kind of hope or blind faith. And it’s the device that connects Weber and Greta after an all-too-believable act of bastardry by Hahn to place the doctor as an inmate of Buchenwald to treat his wife. The machine’s name jars and the quackery feels a bit grafted on (although subsequently I did learn that healing frequency generators do exist). The novel is otherwise adeptly plotted and the fictional component is neatly tied-off at the end. It takes its time, affectively so: the first reference to the camp crematorium’s chimney is on page 142, and it is all the more ominous for that.

The novel is structured in ten parts with instalments of these four narratives (Weber’s, Hahn’s, Greta’s, and the one thousand citizens’) in each, not always in turn. There are plenty of reading breaks therefore. Two of the narratives are openly dated post 1945 so we know from the outset that these characters survive the war. This is a novelistic risk but Remote Sympathy is not a thriller: how is the tension.

Hahn’s narrative takes the form of an interview. He is a fictional character but some of his dialogue, spoken to an unnamed interviewer, appropriates actual testimony from the American Military Tribunal’s 1947 war-crime trials at Dachau. This is chilling and highly effective. Hahn seems not to have suffered any moral injury. We see him and his appalling denial in his own words: remorseless, deluded and self-pitying. He was a blithe functionary, an actual counter of beans, still trying to balance the books with the war lost. And yet he was a dedicated (if uber controlling) father-husband. Karl-Heinz has a set of wooden toy animals that were handmade by his papa: animals for a putative Noah’s ark that Hahn never gets around to making as the pressure of work consumes him. Here Hahn explains why he chose to carve from oak, but Chidgey’s intimations are more subtle:

I’d have liked to work in beech – I thought it would make a nice memento of the place when we were no longer living there – but it was so dense and hard and fine, such an unforgiving wood. I couldn’t get it to behave, and I was forced to dispose of my first disappointing attempts.

There is no ark to save the Nazis. Hahn consoles himself with another souvenir: his private collection of gold pieces fossicked by the camp dentist from the mouths of prisoners.

Remote Sympathy is just as concerned with the proximity of evil as with its banality (to borrow Hannah Arendt’s phrase). A zoo (animals again) abuts the camp, a surreal recreation for the employee families. Greta takes Karl-Heinz for what turns out to be a queasy picnic. Buchenwald can be seen from here, and thereafter, cannot be unseen or un-smelt.

Finally we sat down to eat, and I bit into a sandwich. The bread had gone dry in the heat, and the butter tasted curdled; nobody else seemed to mind, but it coated my tongue with a slick of grease, and I wanted to spit it all out. I swallowed, and felt it shifting down inside me in a hard lump. I swallowed again. Beyond the electrified fence, the smoke from the chimney was thickening, darkening. A blur of grey feathers.

Much of the novel is written in this kind of plain English, which lends it a cool tone. The horrors and absurdities of the camp are in plain sight and the reader is rudely awoken to them: the medical experimentation; the circus of interminable roll calls. The historical truth is stranger and so much more abhorrent than any fiction.

Buchenwald was the largest concentration camp in the German Reich by the end of the war. Altogether almost 280,000 persons were imprisoned. More than 56,000 died. Bearing witness is enough for Greta – but it was not for the ‘one thousand citizens of Weimar’.

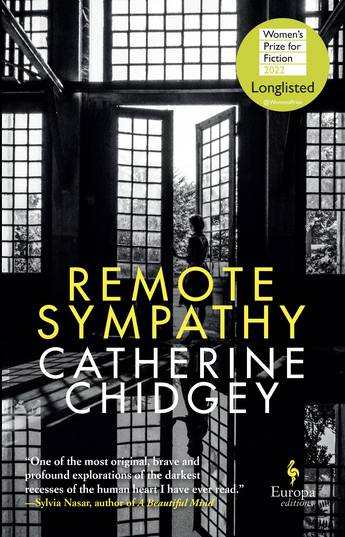

Catherine Chidgey Remote Sympathy Europa Editions 2021 HB 528pp $34.99

Paul Anderson is a freelance editor. He was one of the editorial committee for the 2020 UTS writers’ anthology Empty Sky published by Brio Books.

You can buy Remote Sympathy from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW.

Or check if this book is available from Newtown Library.

If you’d like to help keep the Newtown Review of Books a free and independent site for book reviews, please consider making a donation. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Tags: Buchenwald, Catherine | Chidgey, war crimes, Weimar, World War II

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.