Novelist Bohumil Hrabal’s memoir explores the roots of cruelty by examining the author’s relationship with his many cats.

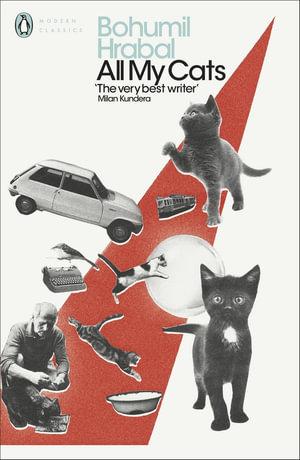

Published in Czech in 1986, novelist Bohumil Hrabal’s non-fiction work All My Cats is now available in English, translated by Paul Wilson, and adds to this Czech master’s growing collection of works in English.

This short book, though, is not a straightforward, heartwarming, animal memoir.

Bohumil Hrabal is famous for toying with his readers and upsetting expectations, as cats toy with prey. He reels out a benign narrative and, when we feel at ease, slams down the fatal blow. His best-known work, the 1965 novel Closely Observed Trains, begins as a wry, funny, coming-of-age story. It ends as a chilling tale of cynicism, a portrait of an innocent cruelly manipulated for political ends unequalled in modern literature, except by Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent.

All My Cats starts with a charming, bucolic scene. Hrabal travels to his country farmhouse in Kersko, an hour from Prague, to be greeted by five cats, strays that share the rural writing retreat.

There are detailed, loving, sometimes comic, descriptions of their intimate life:

When it rained, I’d dry their paws with a dishcloth, because when morning came, when the fire died out, all five cats would jump into bed with me.

But in typical Hrabal fashion, the narrative turns dark.

Worries about his cats plague him. His primary residence is in Prague. Are the cats safe while he is away? How will they survive if he never returns? What if he dies in a car crash on the way to Kersko? As a precaution, he takes the bus. But what if the bus crashes? He sits in the safer middle seats. His anxiety becomes cosmic, universal. He is haunted by ‘images of the horrors that could happen, not just to my cats but to all cats’.

This catastrophising is a little strained. But, as Hrabal shows, the threat to cats in 1960s Czechoslovakia was real, especially in the countryside. Hunters received bounties for dead cats, and catmongers roamed the countryside stalking strays to sell for scientific experimentation.

The most pressing threat to the cats, though, is Hrabal.

Indulged, uncontrolled during their meshugge Stunde (or ‘crazy hour’), the cats wreck the cabin. They foul the beds, the kitchen, the carpets, everywhere except their litter tray (Hrabal treats them to warm milk, not realising cats are lactose intolerant). The place stinks of cats. They squabble, and he must referee. A lawsuit seeking to protect the local birdlife targets his cats. And Hrabal can’t stop thinking about them. He obsesses about his brood and is unable to write.

‘What are we to do with all these cats?’ his wife asks after each disastrous episode.

He decides to find new homes for some of them. But he feels guilt at abandoning his beloveds. When the cats return, unable to settle into their new homes, Hrabal senses their resentment at being rejected by him. The old warmth is disappearing. The charming scene is beginning to unravel.

And then the final blows. Hrabal’s favourite cat falls ill and turns violent. Unexpected litters arrive. The cats’ cruelty to innocent prey horrifies him.

Hrabal’s passion becomes a burden. What is he to do with all these cats?

His response is cruel violence.

Why?

It’s the question Hrabal asks himself and becomes the central theme of the book.

At this point, it’s necessary to say that the descriptions of violence against animals are graphic. Avoid All My Cats if this might disturb you. (I won’t describe the acts). I find Hrabal’s hard-won explanation of the roots of his cruelty convincing, moving, and insightful. But the violence is shocking, and none of the genuine insights may be worth the pain for you.

Hrabal finds his acts shocking, too. After each episode, he dips into suicidal despair.

At first, he tries to convince himself they are necessary, the right thing for society. Humans justify violence to other humans in the cause of social outcomes. Why is violence towards animals any different? It is in society’s broader interest that he control his cats, even if it requires cruelty.

But Hrabal is too aware of twentieth-century history and its devastating impact on Eastern Europe to be convinced by this argument.

When he commits cruel acts, he doesn’t think about the consequences for society. He is not calculating. The violence is visceral, performed in a dream-like state, as though possessed. He feels predestined — ‘no more than a plaything of forces I could not control’, fated to ‘murder love’, a ‘sinner’ whose guilt is preordained. Again, if this sounds over the top, Hrabal reminds us that existential guilt is deep in the modern psyche, in words reminiscent of Prague’s most famous writer:

… in my life I had often been accused of things I had not done, accused merely because I existed.

A random act seems to confirm this metaphysical turn. The car accident he has dreaded occurs, and he survives. He views the near-fatal crash, the result of a truck driver trusting blind luck, as punishment from heaven for his cruel acts. The gods are satisfied. Elated, he returns to his cats.

But metaphysics offers only a brief respite. It is another facile explanation, exposed in the book’s epilogue.

The book’s final part describes a scene with another animal, a swan stranded in a frozen lake. Hrabal attempts to save it. But, hurting from the car accident, afraid he will break the ice and fall into the freezing lake, convinced the swan will crack his skull with its beak, Hrabal leaves the bird. In the pub that evening, he hears a story of injustice during the Nazi occupation. The teller challenges Hrabal to write about it, to cease being the ‘king of comedians’ (a reference to Vlasta Burian, a Czech footballer, comedian, film star and Nazi collaborator).

He could do more, he realises. But he doesn’t choose a grand political statement. He attempts to free the trapped swan.

The tale of the swan and its outcome reveals the source of Hrabal’s heartless cruelty. Hrabal is guilty. Guilty of cowardice. He lacks the courage to do ‘everything I should have’.

There are resonances with Czech politics, of course, as the story of the occupation suggests. Hrabal also refers to the judicial murder in 1950 of democracy activist Milada Horáková. But this book is about everyday failures of courage. The way those we love most, sometimes those least able to defend themselves, bear the burden of our fear and cowardice, often expressed as cruelty. And the evasions we use to justify it.

In Prague, there is a mural of Bohumil Hrabal with his cats. It’s a brilliant piece of public art. Chin down, stern-faced, the writer stares back at us. Thin yellow lines, like parasitical plants tying him to the earth, trace his lower half. To his right, also in yellow, is his silhouette. Three cats hold our gaze with typical feline directness. The image suggests something of the uneasy conclusion of All My Cats. Guilty, shadowed by a bold but empty self-image, Hrabal faces, and lives with, unpleasant truths about himself. Although unsettling in parts, All My Cats is a wise account of the roots of cruelty by one of the twentieth century’s great writers.

Bohumil Hrabal All My Cats Penguin 2020 PB 96pp $19.99

David A. Mitchell lives in Sydney, Australia. He writes fiction and has published poetry in Coven Poetry and is soon to be published in Wind-Up Mice Journal. His reviews of opera and music appear on the Classical Music Daily website. In 2020 David participated in Writing NSW’s Year of the Novel with renowned Australian novelist Emily Maguire. You can visit his website here and find him on Twitter @dmit131

You can buy All My Cats from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.

If you’d like to help keep the Newtown Review of Books a free and independent site for book reviews, please consider making a donation. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Tags: animal cruelty, Bohumil | Hrabal, cats, Czech writers, memoir

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks great review. I’ll this one to my books to read