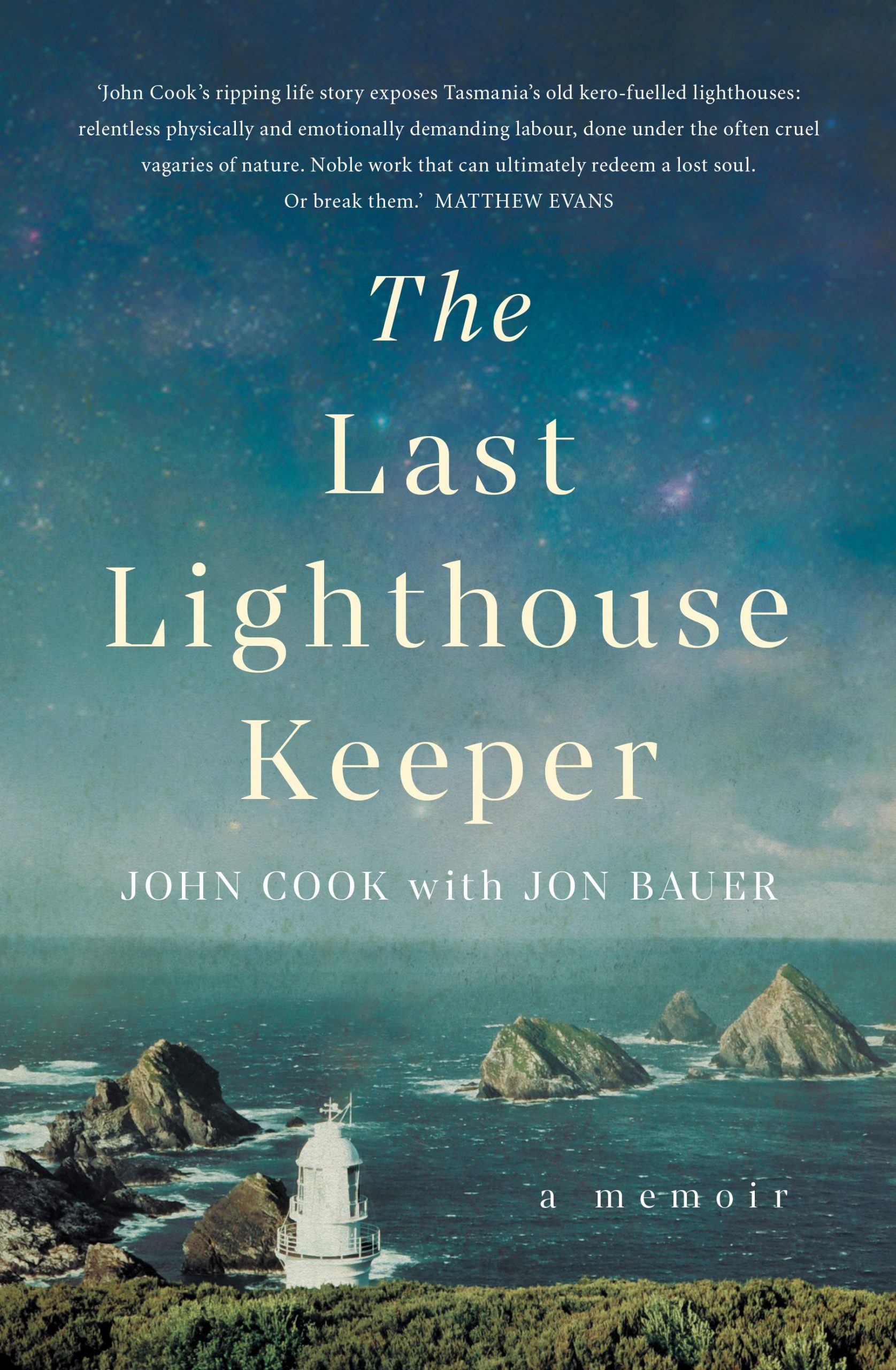

PETER O’BRIEN Bush School and JOHN COOK with JON BAUER The Last Lighthouse Keeper. Reviewed by Ann Skea

These two memoirs of life in remote parts of Australia reveal the challenges of isolation.

These two memoirs of life in remote parts of Australia reveal the challenges of isolation.

By the time Easter approached… I was feeling quite desperate: I had no company of my own age, I had an improper diet, I spoke with other adults only on Sunday afternoons for a few hours at most, and I lived in a tar-paper cubby. — Peter O’Brien

I played a lot of patience on that island. A lot. I tried cheating at it, too. You can’t. It’s too complex to know if your intervention was for better or worse. I came to realise over the years that life is like this, too, and can’t be cheated. — John Cook

These may sound like familiar accounts of being in a coronavirus lockdown, but in fact they are both memories of things that happened more than 50 years ago. Bush School and The Last Lighthouse Keeper are memoirs and each records the experience of living and working in an isolated place away from family and friends. They are very different books but both are fascinating, and both recall a time when there was no internet, no mobile phones, when landlines if they existed were party lines, and long-distance phone calls were expensive. Modes of transport, too, were very different and often unreliable.

Peter O’Brien was a 20-year-old city boy with a rich social life. After completing his training as a teacher, he had spent two years teaching in a busy inner-city school, but ‘because of bonding arrangements that young teachers signed to receive financial support in training’, he now had to complete at least two years teaching in a country school. Peter’s first sight of the tiny, remote village of Weabonga was not encouraging. Arriving in the mail car with the local postman after a circuitous drive through the high tablelands of New South Wales, mostly along gravel roads where ‘traffic was spare, almost non-existent’, they skirted the unfortunately named Swamp Oak Creek, and Peter saw:

… a tumbledown group of tin huts on the right, a shabby weatherboard house to the left… a largish, falling apart tin shed that might once have been a hall and, opposite, a tennis court behind sagging chicken wire.

The timber cottage where he expected to live for the next two years was in bad repair, and the ‘welcome’ he received from his landlady was abrupt. When she took him through the dark house to his room, he encountered a makeshift enclosure on the veranda with just a bed in it – nothing else. From then on the landlady, her monosyllabic husband and their three children kept away from him. He ate alone, and meals consisted of stewed rabbit and squash, daily, and stale bread and rabbit sandwiches for lunch.

Luckily, the one-room school was in good repair, and the children, 18 of them aged from five to 15 from scattered properties around the area, wanted not only ‘to enjoy spending time with each other but they also wanted to learn’.

As an inexperienced teacher, devising a program for this wide range of ages and development, and with no-one to ask for advice or share ideas with, Peter constantly worried that he might not cope. He writes vividly of the ways in which he used the energy and curiosity of the children to implement an innovative child-centred program that not only kept the children interested and happy but also conformed to the Education Department’s curriculum. The children blossomed but, for Peter, the stress and isolation, the lack of guidance, adult company, leisure activities and intellectual stimulation, together with his terrible living conditions, eventually convinced him that, for the sake of his mental and physical health, he must resign. Fortunately, a young man from a nearby farm made contact with him and invited him to join the local rugby club, then, hearing of his predicament, suggested that he come and live at the farm he and his two sisters were running for their elderly father. This turned out to be a happy solution to many of Peter’s problems.

Peter’s concern and affection for each of his young students is very apparent. He writes of their daily interactions, of some of the methods he used to teach them, and of his own exploration of the local area, which was once a thriving gold-mining hub; and of its history, which had shaped the people and the politics of the area. Many of the children’s parents had lived through the war and the Depression and had experienced extreme poverty, and they had passed good values on to their children. Saying goodbye to Weabonga at the end of his two-year stay, Peter noted that the children had changed over the years, grown more confident and knowledgeable, but they had always been tractable and cooperative:

As country kids, they were delightful, happy people, slower in their ways than city kids might have been, more circumspect about relationships with adults. They were innocent, guileless, and mainly free of negative feelings and thoughts, developing as individuals whom, I believed, would grow to be wonderful adults.

‘Well done parents,’ he says.

John Cook’s account of isolation as a lighthouse keeper on Tasman Island is very different, and his memoir begins with an account of the breakup of his marriage and his traumatic separation from his three young children. In 1968, partly to cope with this loss, he took the job of lighthouse keeper on Tasman Island – ‘a rough and trying lump in the middle of the Southern Ocean’. In his Prologue he describes how:

John Cook’s account of isolation as a lighthouse keeper on Tasman Island is very different, and his memoir begins with an account of the breakup of his marriage and his traumatic separation from his three young children. In 1968, partly to cope with this loss, he took the job of lighthouse keeper on Tasman Island – ‘a rough and trying lump in the middle of the Southern Ocean’. In his Prologue he describes how:

Some nights I’d lie on that flimsy balcony, almost a hundred feet above the ground, and roar for you. The sky would be doing its slow roll, the stars strewn, nothing between me and Antarctica but the raging of the ocean. I’d feel like I was in thin air. Suspended from the tall, hollow tower by just a few strips of steel.

Understandably, this is a memoir full of sadness and storms but there are also idyllic passages where Cook describes the land, the sky, the sea, and especially the birds and animals he loved. His experiences of the difficulties of living in such an isolated spot are different to those of Peter O’Brien, but equally psychologically challenging. His descriptions of the damp and mould-infested accommodation, the constant hard work of keeping the light functioning, and, especially, of the terrible weather, are so chilling that it is hard not to shiver just reading them.

Just getting to the lighthouse in the first place was dramatic – a rough sea-crossing, reaching land via a flying fox in a basket strung on an overhead wire rigged from ‘a rock jutting up from the seas, to a landing 30 metres above the water’, then a near vertical ride in a trolley hauled up the side of the island on a tramway.

Cook was not alone on the island. His de facto wife, Deb, accompanied him. To get the job, he had lied to the Lighthouse authorities, saying they were married, and they were constantly worried that this would be discovered and he would be sacked. There were also two other lighthouse keepers and their wives on the island, but these men were in a state of war with each other, so the atmosphere was disturbed and unfriendly. Work was continuous, day and night – keeping the gas cylinders full that powered the light, winding the weights of the rotation mechanism, cleaning the prisms, making weather reports, and ensuring that everything ran smoothly – but sharing shifts with these men was an ongoing problem for Cook. All this kept him busy, but Deb was left alone much of the time, since one of the wives was suffering from mental disturbance and the other was busy with her two children.

Added to these personal problems was the weather. Just one of Cook’s many descriptions of a storm gives some idea of what it was like:

It was going to be a long night waiting for the roof to come off. The wind did not abate but I had my turn on the tower to do… Well before 3 a.m. I got up and put on all my waterproofs and stepped into the hallway… Glass and rainwater was littered along the corridor. I stepped out and the doors at either end were either off or dangling from their hinges… Walking in wind of 100 knots is extremely difficult. Water was blasting me in the face, as were bits of debris… I had to crawl once I got near the tower… There was a huge increase in wind at the tower and I simply could not get there. It was like clinging to the wing of a jet.

There was dangerous hail, too, and fogs which frequently surrounded the lighthouse, although it could be a sunny day down at sea level. There are descriptions of terrible storm damage and danger, of being cut off by bad weather so that provisions became scarce. But there are memories, too, of whale song, schools of dolphins, a troop of fairy penguins marching over his feet, ‘kamikaze’ mutton birds crash-landing in the scrub, and of a broken-winged bird which Cook nursed back to flight.

Toothache, hernia, appendicitis, unexplained excruciating stomach cramps – the illness of anyone on the island was a constant worry as the boat to the mainland might have to wait days for a storm to abate. Interestingly, Cook notes that each time he went to the mainland, he got sick because he was again mixing with many other people.

Tasman Island was not the only lighthouse where Cook worked, and later he was to witness the electrification of the lights, which he found heartbreaking, partly because it broke the isolation he had become used to but especially because it disturbed the natural ecology of the islands, which he had come to love, and which he writes of glowingly. He hated the changes which occurred with electrification, but he could not tear himself away from the lights. For Deb, they were his ‘other wife’ and she distanced herself from them and from him. Eventually, the stresses of the job and of Cook’s worries about Deb, and about his children, resulted in the authorities recommending psychiatric treatment. But he stayed in the job and by the end of the book there are hopeful signs that his life, and his relationships with Deb and his children, were beginning to regain a happier balance.

John Cook was one of Tasmania’s last kerosene lighthouse keepers.

Peter O’Brien Bush School Allen & Unwin 2020 PB 296pp $29.99

John Cook with Jon Bauer The Last Lighthouse Keeper Allen & Unwin 2020 PB 352pp $32.99

Dr Ann Skea is a freelance reviewer, writer and an independent scholar of the work of Ted Hughes. She is author of Ted Hughes: The Poetic Quest (UNE 1994). Her work is internationally published and her Ted Hughes webpages (//ann.skea.com/) are archived by the British Library.

You can buy Bush School from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

You can buy The Last Lighthouse Keeper from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.