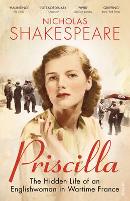

NICHOLAS SHAKESPEARE Priscilla: The hidden life of an Englishwoman in wartime France. Reviewed by Peter Corris

Imprisonment, the Resistance, intrigue – Nicholas Shakespeare peels away the layers of his aunt’s unlikely story.

Imprisonment, the Resistance, intrigue – Nicholas Shakespeare peels away the layers of his aunt’s unlikely story.

In a nice Euro joke, German Chancellor Angela Merkel fronts up to French passport control.

Officer: Name?

Merkel: Angela Merkel.

Officer: Nationality?

Merkel: German.

Officer: Occupation?

Merkel: Nein, just staying a few days.

But the German occupation of France from 1940 to 1944 was no joke, especially to an Englishwoman married to a Frenchman and unable to escape to England. Priscilla Mais was subjected to harsh treatment in an internment camp and, after her release, to many and varied restrictions: she had to report to police daily, observe a curfew, not travel to a coastal area, own a radio or a telephone and was forbidden to ride a bicycle but not a horse. She defied many of these edicts

To have an interesting relative can be a boon to a writer, and well-credentialled English author Nicholas Shakespeare struck gold with his aunt Priscilla.

The daughter of a prominent English journalist and broadcaster, Priscilla, as a result of her parents’ marital breakdown, spent much of her youth in France and in Paris in particular. Tall, blonde and beautiful, she modelled clothes and hung out in fashionable and louche circles. At this point most of the French people she knew had titles and the English, of whom there were a great many in Paris, had hyphenated names. But there was a shadow that persisted throughout her life – the feeling that her father, whom she had adored, had deserted her. In marrying a wealthy French aristocrat much older than herself, she acknowledged that her husband was a father figure. When he, a conservative Catholic in a traditionalist family, proved to be impotent, it was clear that life wasn’t going to be easy. Then came the war and the Occupation.

Shakespeare first encountered his aunt (his mother’s half-sister) when he was a small boy. She was married to Raymond Thompson, a prosperous, jealously possessive, irascible mushroom farmer in Sussex. Spending holidays and weekends at the farm, Shakespeare was intrigued by the still beautiful Priscilla, who could be warm one day and totally withdrawn the next. She appeared to do nothing but swan about elegantly attired, smoke and drink and spend long periods in her bedroom. Among the oddities he observed was her habit of sunbathing naked in a secluded part of the garden and the visits she and her second husband paid regularly to her first husband in France.

Mystery surrounded Priscilla, and Shakespeare, journalist and novelist in his maturity, always alert for a story, felt that one could be found in the life of his elusive, now-dead aunt. It was known that she’d spent four years in Occupied France but details were few. She had been imprisoned twice, but where and how had she regained her freedom? She had driven trucks. In what capacity? For the Resistance?

Probing, Shakespeare learned of a trunk Priscilla had kept in her bedroom. Her stepdaughter gave Shakespeare access and he discovered a treasure trove of letters, documents, manuscripts and photographs that began to fill in the gaps. The papers of Gillian Sutro, a lifelong friend of Priscilla’s, lodged in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, provided further information.

Over time and through many interviews and long hours in archives, Shakespeare unpeeled the onion and discovered startling and disturbing facts about Priscilla’s life. The work was not easy:

I discovered from reading and talking to people that certain sections of the French National Archives in Paris are still closed to the historian … The same secrecy surrounds the police archives or what remains of them – the Wehrmacht when they retreated took back to Berlin the most important files, many of these being shipped on to Russia in 1945 … Most of the Gestapo’s archives in Paris, in particular those concerning the group known as ‘the French Gestapo’ were destroyed in 1944 …

But Shakespeare persisted.

To reveal in a review how Priscilla survived would be to spoil the unpeeling so carefully and dramatically handled by Shakespeare. Her time was fraught – a mixture of ill health, false papers, assumed identities and the constant threat of betrayal. At least once she was in dire peril, making a 100-mile bicycle ride from Le Havre to Paris after D-day.

I hadn’t realised that the Allied invasion was as destructive as the German incursion four years before, perhaps more so. The collateral damage to persons and property was enormous.

Priscilla and her companion frequently had to take refuge in ditches as Allied planes strafed the roads. Back in Paris, recrimination was in full swing and people, particularly attractive young women like Priscilla, were in danger of denunciation as collaborators from people who were often motivated by grievances and jealousy … but not always.

Repatriated to England ‘just in time’, as she announced to a friend, Priscilla settled for the security of a marriage. She tried to write, yearned to be published, but failed. Human-interest articles, travel pieces and short stories were all rejected and her novel was never finished. She battled with alcohol and unresolved issues with her father. Shakespeare observes that her writing wasn’t good but he also seems to be constrained to admit something else that emerges from her hectic story – that she wasn’t very intelligent. She acted as though her beauty absolved her from making considered decisions. At every crucial point she relied on a man to see her through.

Her belief that as a Catholic convert, divorcing her husband and remarrying would condemn her to everlasting damnation, was a big-noting delusion born of low self-esteem and ignorance. A letter to her stepdaughter, who was about to turn 18, contained phrases such as divorce is always ‘a wicked and terrible thing’. Mercifully she did not post it, perhaps recognising that it was plainly stupid.

Her story is thus a picture of times well out of joint and of a woman who behaved, and was often treated, as a child. The best thing Priscilla Mais did was provide the material for her nephew to write a compelling book.

Nicholas Shakespeare Priscilla: The hidden life of an Englishwoman in wartime France Vintage 2014 PB 368pp $19.99

You can buy this book from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here.

To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.