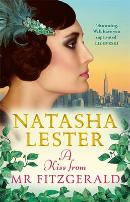

This new novel from Natasha Lester is best read with gin and jazz.

Natasha Lester gives us all the glitz and glamour of classic romance in her third novel, a work of romantic women’s fiction that takes us back in time to the 1920s. There is gin, there is dancing, but there is also a patriarchal structure that suffocates any achievement by women. There are pretty dresses, and shoes to die for, but there are also graphic scenes of childbirth and the callous abuse of women. All these elements are woven together seamlessly.

Lester is undoubtedly a mistress of the romance genre and her novel lets readers know what they are in for from the very beginning. A Kiss from Mr Fitzgerald opens with the main character, Evie Lockhart, dancing on stage. All eyes are on her. She is beautiful, she is glamorous, and she is dancing in a classic 1920s gin joint. But there is far more to this classy showgirl then high kicks and skimpy costumes:

This new novel from Natasha Lester is best read with gin and jazz.

Natasha Lester gives us all the glitz and glamour of classic romance in her third novel, a work of romantic women’s fiction that takes us back in time to the 1920s. There is gin, there is dancing, but there is also a patriarchal structure that suffocates any achievement by women. There are pretty dresses, and shoes to die for, but there are also graphic scenes of childbirth and the callous abuse of women. All these elements are woven together seamlessly.

Lester is undoubtedly a mistress of the romance genre and her novel lets readers know what they are in for from the very beginning. A Kiss from Mr Fitzgerald opens with the main character, Evie Lockhart, dancing on stage. All eyes are on her. She is beautiful, she is glamorous, and she is dancing in a classic 1920s gin joint. But there is far more to this classy showgirl then high kicks and skimpy costumes:

That was a place of discreet money and manners and hidden mistresses, where women called Evie Lockhart fought a battalion of men every day for permission to become a doctor. Inside the theatre, the men had no manners, the mistresses were out on show, the money splashed around like whiskey, and Evie Lockhart was once again fighting, this time to remember that an exchange of dignity for college fees would be worth it.

However, it isn’t the hope of becoming a doctor that keeps Evie warm at night, it’s the thought of Thomas Whitman:Instead she’d lie awake, remembering how often she’d dreamed of kissing Thomas Whitman. And she’d try not to think about the fact that now he knew she worked for Ziegfeld, he’d never want to see her again.

There is no doubt that this is a romance novel and that the reader can expect all the tropes and treats that this provides. Beautiful leading lady: check; two men to choose from: check; a plain-Jane sister: check. Some readers dismiss romance novels as just silly love stories (what’s so silly about wanting to love and be loved?), but Lester provides some searing political commentary that still rings true for the modern age, despite her story being set 100 years ago:‘If you’re rich, charming and a man, you can steal a stuffed cougar, call it a prank, make a donation to the college and then become a banker, in the time it takes me to embroider a hanky.’

Rich men are able to get away with criminal activity and be promoted, while women are subjected to unpaid emotional and physical labour and given little to no credit. Any departure from behaviour deemed appropriate by polite society is dealt with harshly, not only by ostracism but the denial of medical care. It is in fact this repugnant treatment of women that inspires Evie Lockhart to become a doctor:She took off her hat and laid it on the hall stand. She suddenly realised she hated that stand, with its gold Minton tiles and gold-plated drip trays. Who really need their umbrella to drip into a gold tray? Society did. A society that thought Evelyn was not supposed to sit in the dirt and let a labouring mother bleed all over her. She was supposed to run away, aghast, and then faint like a lady. Because an unmarried woman having a baby alone by the river was a position never to be recovered from; it guaranteed invisibility and revulsion, so that every time hereafter, when Rose went to the grocer’s store and was ignored, she would know she was being mocked and judged and declared repugnant, like the cow’s feet the butcher threw away because even the poor wouldn’t eat them.

Evelyn remembered the baby’s eyes, how they’d stared up at her. It was helpless and trusting, yet she’d abandoned it. For its whole life, everyone would treat that baby the way Evelyn had, turning their backs. How could she have left Rose and her baby to the mercies of Charlie and her father? And would she ever be able to make amends?

Evie Lockhart undeniably has a pretty face that can charm any man, but she’s more than that. She’s highly motivated, she doesn’t take no for an answer, and she’s intelligent. She does not spend the whole novel sighing over her lot, she actively pursues her goals. Knowing full well that being a showgirl will ruin her reputation, she becomes one anyway because she is so motivated to become a doctor. This in itself is something she is actively discouraged from doing, but again, she doggedly chases her dreams. During the 1920s, for a woman even to desire to go to university and train in the sciences is a scandal. In essence, Evie Lockhart continually moves from one scandal to another in the hope of becoming her true self. A self that polite society would be unlikely to accept. The novel sets up a series of mysteries. Firstly, who will Evie Lockhart end up with? Charles or his mysterious older brother, Thomas? And then there is the intriguing issue of Rose and her baby. Who was the father? What has happened to the baby? And, of course, how will a girl from a conservative, upper-class family manage to go to university instead of getting married off and starting a family? And the questions and mysteries keep unfolding until the last page. This use of tropes from the mystery genre adds a sense of intensity to Lester’s writing that will keep readers thoroughly hooked until the end. A Kiss from Mr Fitzgerald will be lapped up by not only fans of the romance genre, but those interested in fiction about women’s issues, from getting the vote and the right to education and autonomy, as well as more modern concerns such as internalised misogyny. All these complex issues are explored, with a happy ending and some romance thrown in for good measure. From time to time don’t we all need to read a book that makes us squee with happiness at the end? Natasha Lester A Kiss from Mr Fitzgerald Hachette 2017 PB 384pp $19.99 Robin Elizabeth is the author of Confessions of a Mad Mooer: Postnatal Depression Sucks and blogs at http://riedstrap.wordpress.com about her love of Australian literature, depression, and whatever tickles her fancy bone. You can buy A Kiss from Mr Fitzgerald from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW here or you can buy it from Booktopia here. To see if it is available from Newtown Library, click here.Tags: Australian women's writing, historical fiction, Natasha | Lester, romance

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.