Opus Dei likes to operate in the shadows; Gareth Gore brings its activities – including allegations of human trafficking – into the light.

In 2017 Banco Popular Español, the sixth-largest bank in Spain, collapsed. Gareth Gore, a journalist with the International Financing Review, decided to investigate the reasons behind it. He soon discovered the bank’s longstanding links to Opus Dei, an organisation of the Catholic Church. He turned his focus to investigating the history and operation of Opus Dei, not just in Spain, but around the globe – including brief mentions of its activities in Australia.

Opus Dei (‘the work of god’) was founded by Josemaria Escriva in Spain in 1928. Gore writes:

At its core was the idea of a universal call to holiness. He envisioned a lay brotherhood of men – ‘never-no way-will there be women in Opus Dei’ – who would serve God by striving for perfection even in the most everyday tasks … Escriva’s vision for Opus Dei was a deeply Christian one, embracing notions like compassion, forgiveness, and charity.

The early chapters examine the stuttering process of Escriva developing his thinking on the work of Opus Dei, finding followers and accommodation for them to live in while they performed their holy work. This was difficult during the tumultuous 1930s in Spain, particularly during the Spanish Civil War. After Franco’s eventual victory, and the end of World War II, he was able to proceed with his vision.

Escriva focused his attention on recruiting talented young men at universities. Such men would devote their lives and income to Opus Dei. Following completion of their degrees, they would find employment in leading businesses and, with the passage of time, would be promoted to senior positions that would enhance their ability to provide funds for Opus Dei. Such funds, in turn, would be used to obtain more recruits, acquire more residences, and build or acquire schools and universities to promote its work. Opus Dei would also invest in businesses and obtain shareholdings in leading companies. Such investments would be through shell companies or members of Opus Dei who would do its bidding, with such intermediaries providing it with protection from potential legal action if something should go wrong.

Crucial to this strategy was Banco Popular. An increasing number of Opus Dei members joined its board and Opus Dei companies invested in its operations. For more than 50 years Banco Popular provided favourable terms to such companies and regularly donated large sums from its profits to Opus Dei foundations and charities. Banco Popular bankrolled Opus Dei’s growth – residences, schools and educational institutions – not only in Spain but across the globe.

Escriva developed intricate rules to control the lives of disciples, which reminded me of how Mother Russia operated under Stalin and other leaders.

… at the heart of the organization lies an elite corps who live highly controlled existences. Having taken vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience, this elite group live according to a dystopian set of rules and regulations … Nine thousand members live this tightly controlled existence of prayer and indoctrination, where almost every move is meticulously prescribed and watched over, where contact with friends and family is restricted and monitored, and where their personal and professional lives are subject to the whims and needs of the wider movement.

Gore discusses a taboo that lies at the heart of Opus Dei, which he sees as a fundamental problem for it:

At the root of this taboo is the foundational myth that Escriva had established [Opus Dei] according to a vision sent to him directly from God. This myth created an aura of infallibility around everything to do with that vision … Escriva had been a mere instrument of God, and to question anything about Opus Dei was to cast doubt on God Himself. This way of thinking had permeated the organization for decades, creating an expectation of blind obedience and quashing the smallest element of dissent about the rituals, customs, and structure that underpinned life within the organization.

The residences where Opus Dei members live are serviced by squads of females, who tend to the needs of male members, but live in separate quarters. To the extent that there is a need for interaction, these servants are required to advert their gaze. Girls as young as 12 and 13 from low socio-economic backgrounds are recruited with promises of education and a career. Their lot is to work 15-hour days, seven days a week, with no pay, cooking, cleaning, and washing. They have no rights and are told if they leave, their families will go to hell.

These girls and women are transported to different residences within and between different countries. Gore maintains that the control and transportation of these servants transgresses the United Nations Convention against Human Trafficking. In his final chapter, he examines 43 Argentinian women who initiated a class action over their lack of compensation for working as virtual slaves in Opus Dei residences.

Gore draws attention to examples of sexual abuse of (male) children and females by Opus Dei members and priests. Opus Dei’s usual response to such allegations is to move the persons concerned overseas or to maintain that abuses against male children were examples of homosexuality rather than pedophilia.

Gore also draws attention to some more controversial moments associated with Opus Dei and the Vatican. On 17 June 1982, the body of Italian banker Roberto Calvi was found hanging beneath Blackfriars Bridge in London, ‘his pockets stuffed with thousands of dollars in foreign banknotes’. He had been the Chairman of Banco Ambrosiano and had authorised the transfer of hundreds of millions of dollars to overseas shell companies owned by the Vatican. His son revealed that ‘Calvi had been negotiating with Opus Dei to help bail out the Vatican just before his death.’

Another example concerns the arrest of Robert Hanssen as a Russian spy in February 2021. From 1976, Hanssen worked in counterintelligence for the FBI. Following his arrest, it was discovered that he had begun spying for the Soviets in 1979. As he embarked on what turned out to be a career of 20-plus years as a spy, his wife advised him to confess to his Opus Dei priest. The priest initially advised him to turn himself in to the authorities. The following day the priest changed his mind and advised Hanssen to ‘give away to charity any money the Russians paid him and move on with his life’. Gore comments that the priest, ‘as the most prominent Opus Dei figure in the United States … must have known that a scandal involving one of the movement’s most prominent families would reflect badly on’ Opus Dei.

Gore also takes us through the final days of Banco Popular in 2017. On the surface this may have seemed a major setback for Opus Dei. However, the organisation had opened up a new source of finance, one even more secure than a bank: American billionaires who wanted to return America to conservative Christian values. As Gore says: ‘positioning itself as a champion of disgruntled Catholic billionaires offered Opus Dei a new lease on life’.

Most of the latter chapters examine the operation of Opus Dei in America. Moneys raised were funnelled into various foundations and think tanks in pursuit of a conservative Catholic agenda. Gore focuses on how Opus Dei and conservative operatives concentrated on the appointment of like-minded judges to the Supreme Court with the object of overturning the abortion rights contained in the Supreme Court’s Roe v Wade decision of 1973. Six of the present judges have Opus Dei connections – Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, John Roberts, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett.

Consistent with the early operation of Opus Dei, the American venture is using this wealth to attract bright young men to be educated and enter organisations to replicate the victory against Roe v Wade ‘in other sectors of society, such as education, the media, Wall Street, and Silicon Valley’.

One of the strengths of Opus is how Gore situates Opus Dei’s political machinations within the Vatican. Its progress has been thwarted when there have been more liberal popes, such as Paul VI (1963 to 1978), and enhanced under traditional conservative popes such as John Paul II (1978 to 2005). The current pope, Francis, has acted to downgrade Opus Dei and its position in the Church. Given this, Gore observes, ‘the best hope for Opus Dei … hinge[s] on Francis’s dying before he can follow through on his clear desire to clip [its] wings … and end its abusive practices’.

In the final paragraph he writes:

If Francis dies before real reform happens – and if his successor proves unwilling or unable to carry on his initiative – then Opus Dei will emerge from its near-death experience invigorated and defiant. Revitalised, backed by its army of donors, the movement will power forward with its plans to re-Christianise the planet, whether that’s what people want or not. Gay marriage, secular education, scientific research, and the arts will fast become its next targets. Given its supporters’ unexpected victory over abortion, it’s quite possible Opus Dei and its sympathisers could mastermind equally devastating victories in those areas.

It would be reasonable to assume that most people know little about Opus Dei, its objects, history and modus operandi. Opus is a thoroughly researched, accessible and readable account of its activities and what is in store for the world if it achieves its ambitions. Gareth Gore has done a major service in bringing its operation into the light of day. The everlasting blessing of knowledge.

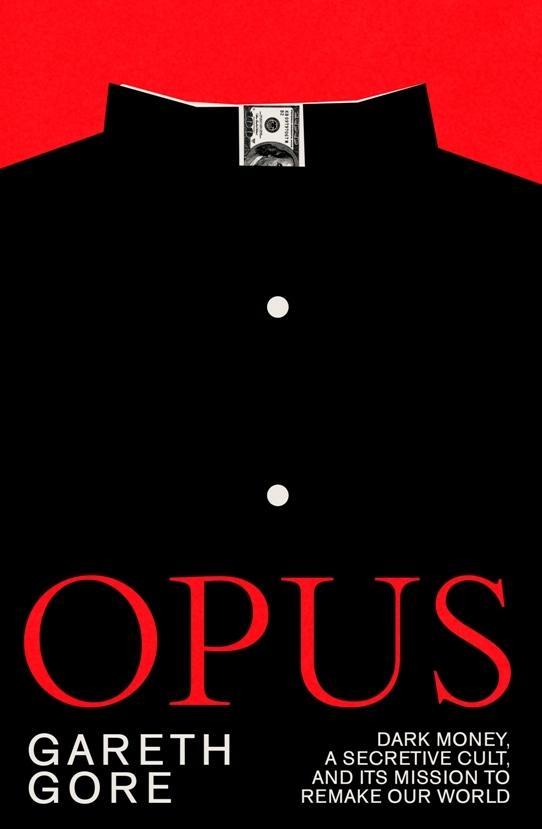

Gareth Gore Opus: Dark money, a secret cult, and its mission to remake our world Scribe 2024 PB 448pp $39.99

Braham Dabscheck is a Senior Fellow at the Melbourne Law School at the University of Melbourne who writes on industrial relations, sport and other things.

You can buy Opus from Abbey’s at a 10% discount by quoting the promotion code NEWTOWNREVIEW.

You can also check if it is available from Newtown Library.

If you’d like to help keep the Newtown Review of Books a free and independent site for book reviews, please consider making a donation. Your support is greatly appreciated.

Tags: Banco Popular Español, Catholic church, Gareth | Gore, human trafficking, Josemaria Escriva, opus dei, Pope Francis, Vatican

Discover more from Newtown Review of Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.